That's among the takeaways from "Shifting Neighborhoods," a new report from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. And it rings true to a pair of Latino community leaders, whose organizations have experienced gentrification, too.

"In the summer of 2017, we sold our building in Baker, where we'd been for 42 years, and moved to Westwood," notes Monique Lovato, CEO of the Mi Casa Resource Center. "So you could say, in a way, we were gentrified out, because the people we served were moving in all directions."

Adds Mike Cortés, executive director for the Colorado Latino Leadership, Advocacy & Research Organization, formerly known as LARASA, "We used to be located on the north side of Denver, up close to the Highlands, which is an area that's still undergoing intense gentrification and densification. But we found ourselves getting distant from the people we mean to serve. So some years ago, even before it got as gentrified as it's gotten now, we moved over to the Baker neighborhood. Then, three and a half years ago, we moved from there because, again, the people we're driven to serve aren't there anymore."

Today, Cortés points out, CLLARO is "located in Montbello — a neighborhood that I'd very much like to see intact."

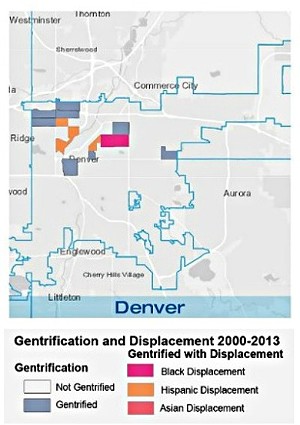

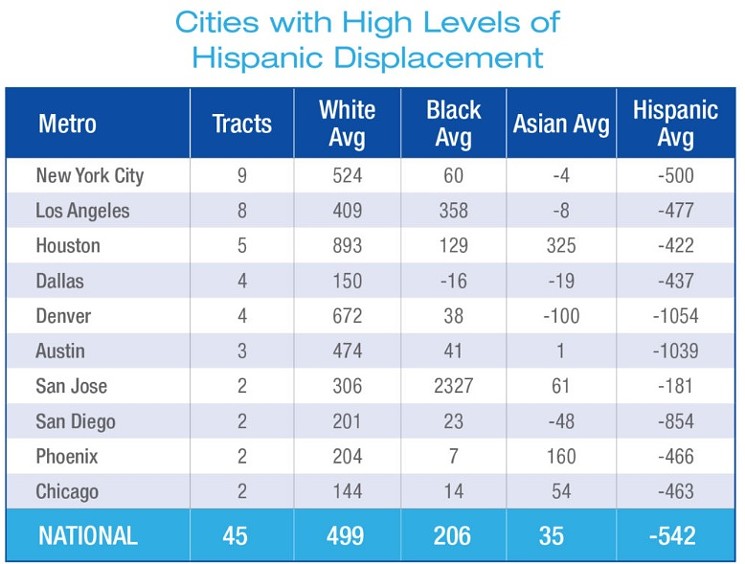

Maintaining such communities can be difficult when gentrification is in full swing, as it is in five traditionally Latino tracts seen in this "Shifting Neighborhoods" graphic. In these areas, Denver experienced what the study's authors characterize as "the highest average decreases of Hispanic residents" in such areas, at 1,054. The next closest total per tract was recorded in Austin, Texas, with 1,039, and the average residential decrease in such gentrifying tracts across the country was 542.

This is not to suggest that all Hispanics are abandoning Denver. In fact, figures supplied by Cortés show that between 2011 and 2017, the percentage of Latinos relative to white residents in the Mile High City rose by nearly 8 percent — not quite as high as the 10 percent bump in Adams County, but larger than the 6 percent growth registered by Weld County and the 4 percent boost in Arapahoe County.

But in specific areas, where gentrification is at its most intense, longtime Hispanic residents are under pressure to leave in order to make room for folks with higher incomes. Those who own their properties and are able to sell them to developers may benefit financially from this phenomenon, Cortés acknowledges. But he stresses that this experience is hardly universal — and those in less advantageous circumstances can suffer a multiplicity of losses.

"We've been concerned about this for a while, as have other Latino advocates here in Denver," he allows, "because it's a burden on Latinos to lose neighborhood-based community, the mutual support networks that are already in place, and ready access to services they're already familiar with."

Moreover, he continues, "when people get displaced into other areas, generally outside the City and County of Denver, they're scattered. A lot of the mutual support networks are weakened. Plus, the way in which folks are gentrified can be a problem. In neighborhoods that are being targeted, especially by speculators, Latinos are likely to be persuaded to sell for less than they could have gotten if they knew the market better, and the speculator is in a position to make a bigger profit. That's not doing our community any favors, either, given our relative low wealth and income."

He cites Montbello, CLLARO's current home, as an example.

"It's undergone demographic changes over its history, but it's a special place," he says. "It's a primarily minority neighborhood: 60 percent Latino, most of the rest African American, and a small percentage of various backgrounds, including immigrants and Anglos. There are scatterings of wealth here and there among people who like the neighborhood, but, in my view, it hasn't gotten its fair share of services from the city and from DPS [Denver Public Schools] — although it's had a chance to develop some social infrastructure and community organizations. We're pleased to be one of those organizations, and a few of these nonprofits collaborate together with the Montbello Organizing Committee on programs we and others operate that help residents address important issues."

At the same time, however, "I hear anecdotal reports of speculators coming in," he continues. "They're keeping an eye on the new Peoria light-rail station, its close proximity to Peña Boulevard and the airport, and the rising real estate market in general. It's not rising quite as fast as it had been, but it's still going up as opposed to down — and my sense is that Montbello is being targeted by folks who would ultimately like to make some money and, in the course of doing that, they may change the demographic makeup of the neighborhood, intentionally or not."

For Cortés, these signs represent an unfortunate brand of déjà vu.

"This has been the experience of our organization," he confirms. "We've been chased out of one neighborhood after another just by circumstance, not by force. We're very happy to be in Montbello, but we'd like city planners to do what they can to make it attractive and feasible for people to continue to find affordable housing in Montbello. The competitive markets in real estate being what they are, we see a need for community and government intervention to make sure that the needs of folks who don't have as much to invest in housing continue to be met in this neighborhood. We need to be very vigilant in Montbello to make sure that people who would prefer to remain there find it economically attractive to do so."

This graphic from the "Shifting Neighborhoods" report shows the impact of gentrification on Hispanic displacement in numerous U.S. cities, including Denver.

Westwood, where Mi Casa is presently located, is a case in point, she emphasizes. "This neighborhood has historically been populated by Latinos, Vietnamese, Koreans, Chinese immigrants. But Westwood is also vulnerable to gentrification and involuntary displacement, because it has had one of the highest foreclosure rates in the state. According to the task force I sit on, one in six homes in Westwood has been turned over — flipped or renovated, either moderately or completely, and sold as a result of the foreclosure crisis. So we have people who have lost their homes or struggled to stay in them — and then the flippers came in."

Lovato tries not to demonize every alteration to the status quo. "I have this principle that we're all gentrifiers — even Mi Casa. We moved to Westwood to a new building. Now, I wouldn't say we pushed people out, because this was a vacant lot before, and we're trying to help people stay. But we changed the neighborhood."

The key, in her view, is to make such shifts in a way that enhances the community instead of turning it into something completely unrecognizable. For instance, the Mi Casa complex, which represents a $14 million investment aided by a $400,000 City of Denver loan that will be forgiven if the organization stays in place for five years, includes 42 affordable housing units. Residents aren't required to use Mi Casa as a resource, but it's available if they'd like to in the most convenient setting imaginable. In that sense, Lovato says, "I think our building is an improvement over what was here before, and the services we provide are a big value-add to this community. We brought a free legal clinic, job training, small business services and development. We've brought a lot of good things the neighborhood now has easier access to than it did before."

Denver is pushing similar developments involving nonprofits — a new complex for Clinica Tepeyac near 48th and High among them. Additionally, there are numerous "opportunity zones" in the city that are intended to attract investment — although Lovato warns that this concept must be handled carefully.

"State and local governments really have a role to play in managing the opportunity zones they put on the map," she maintains. "There need to be some guardrails around them, because it could be a way for private developers to come in and own wealth in the community and not necessarily have it benefit the low- and moderate-income families that opportunity zones were intended to serve. That's an issue on the horizon that could be a great way to build wealth in the community or strip wealth out...that whole unintended consequences thing."